#32 - we can perform into being

Kathak, Akanzyla, and the latest revolutions

I took my first Kathak class when I was six years old. Joanna Das (now Joanna Da Souza), a white Canadian-born woman who pursued a life-long study of Kathak was starting to teach at my eventual high school across the street. My bestie, Anushka, and I, accompanied by our mothers, entered into a grey-on-grey gymnasium for a trial session, which set us off on a nearly decade journey of learning to tell stories through dance. I’m not sure how we felt about a white lady teaching us Indian classical dance, and how we would negotiate that today, but back then we all fell in love with Joanna.

From then, on Wednesday evenings and later, Saturday mornings, we would strap on rows of gungroo around our ankles, each line of bells gifted as a symbol of maturity in the practice. Ta thei thei tat. Right, left, right, left. In the early years, our feet would lift and return to the earth, again and again, until the new rhythms of footwork merged with the body, rendering the mind irrelevant. In time, ta thei thei tat, turned into ta ta thei thei tat, thei thei ta ta tat, sped up double time, triple time, and across the infinite possibility of patterns within two beats and two feet. The arms would eventually join, swaying between lightning hits and silken flows, always holding iconographic mudras to further convey the hidden poetics of a story.

Kathak is one of 15 Indian classical dances, originating from Uttar Pradesh, which literally translates to story in Hindi (katha). Its essence is that of a tree; the legs a strongly rooted trunk, and the arms, curious branches swaying and resisting in the wind. The form finds pride in its sequences of swift turns; sometimes in rows of 25, garnering roaring claps from otherwise conservative audiences. ‘Find a point on the wall, and do not look away,’ Joanna would say. Turns were all about locating a central place of conviction and returning back to it even after traveling 360 degrees in orbit. When the feet, the arms, and the turns were baked, the final touches were pairing the neck and the eyes; using the offering and withdrawal of the gaze as the ultimate language of power.

I haven’t thought about Kathak for a while, but a friend brought it up on our first pandemic patio outing last Saturday, and it got me remembering. About how dance and performance were my first language with myself. About how my life was the performance, and the stage was my own. And about how dancing, the only thing that comes to me with blessed ease, feels unfamiliar and off-key through a year of sedentariness.

I wonder if our moms knew. That as ‘women,’ our performance of gender would expect pleasant smiles and uncreased skirts, emphatic responses and perpetual hairlessness, an assumed fortitude and patient care. All while our diaphragms were squeezed so that each breath was a labour unto itself. It’s different now in some ways, but how could they have known that. They gifted us the stage, a black box to stretch, take up space and create the rules rather than merely live within them.

In diasporic households, learning an Indian classical dance was a right of passage and preservation. Along with Kathak, I competed in Gujarati folk dance competitions (casually organized by caste and samaj), performed during auspicious occasions at the temple, Diwali variety shows, and weddings, and eventually in cross-university dance competitions. In these performances, I always had a tendency to screep, a word I coined with some friends to define the act of ‘scope creeping,’ i.e. going way, WAY beyond the necessary call of order. A casual Diwali fashion show in a different high school gymnasium turned into a full-on production of DDLJ, and our UofT dance troupe once built a rotating pyramid for a 10-minute dance performance. I’m not sure where the tendency to screep comes from, but I suspect it is somewhere between just being extra to be extra, a competitive nature, trying to prove something, wanting to have maximum fun and maximum wow, and having scarcity on when I would be on the stage next.

After 20, I barely danced or performed, except at the occasional wedding, abandoning Kathak for the allure of a part-time retail job and the financial freedom it promised (they made us work on Saturdays). It sounds tragic, and in some ways it was, but my fight for freedom was nothing short of a riptide and that was important too. Though it meant I never became a professional dancer, at that point in my life, I didn’t even know that was a legitimate option.

This time next week, I will be performing live as Akanzyla, an Indian climate refugee living in 2050 T’karonto who is reorienting to a life of virtual community, care and self-sustenance, while negotiating the realities of climate collapse and restoration. It is not a dance per se, but more like one of Kathak’s swift turns that needs full devotion to my centre. Performance art is the practice of creating a world, with rules and permissions, and then living in it with an audience; it is not meant to be rehearsed. I am terribly nervous; not unlike the nerves when you’re waiting in the curtain wings before someone yells, ‘now! now!’ as your cue, and just like that you are flying across the stage - your face blinded by the spotlight and frozen in glee.

Back then, performing was tied often tied to clout and even trophies. My parent’s basement still has a glass case of ephemeral moments captured by mini wooden pedestals with plastic golden figurines sitting atop. Now, it feels like this performance is mostly for me, and the invisible net of consciousness that we are always shapeshifting. I will invite an audience into this little world I’ve dreamt up, with the help of Macy’s speculative research wizardry, because I want us to remember that we can perform new ways of being, into being. I want to remember too.

It seems like there are versions of ourselves that we let go of, necessarily, and others that we return to. We might say one is more ‘true’ than the other, but I think they all matter - even the ones that make us long for the other. Even in the return to a part of ourselves that we miss - our relationship with it has changed, as we have changed. Life is certainly a performance, but it is also a dance.

Much love,

Hima

P.S. Please pop into Akanzyla next week for 10 minutes, 20 minutes, or you know, having it running parallel to your browser all day :) :) here is the link to register for the Zoom.

Real-time Revolutions

Bye Colonial House: The video of Mumilaaq Qaqqaq, the former NDP MP of Nunavut, giving her final remarks after departing Parliament is circulating and if you haven’t watched it, I suggest you do because not only did she not hold back, she made truth-telling history. This goes into the archives on the road to reclaiming Indigenous sovereignty and resurgence over this land, and when we finally dissolve the colonial structures of this country. ‘Every time I walk through these doors, not only am I reminded of the clear colonial house on fire, I am already in survival mode’

No one is ever just nice: The underbelly coming to the surface as more children’s bodies are devastatingly being identified in former residential schools across Canada and Human Rights Watch released a report today on the horrifying conditions of immigration detention in Canada. This might feel like a disappointment to Canada’s nice and friendly image, but like should you ever trust anyone that self-identifies as nice? No. The answer is no.

We demand more! Juneteenth became a national holiday in the US, and ‘Cancel Canada Day’ is trending to relinquish us from celebrating this colonial state and honour the relentless grief that Indigenous communities and anyone with a heart are experiencing right now. In Victoria, there was a bizarre announcement about canceling Canada Day, but then not really canceling it? by suggesting to use the day to ‘explore what it means to be Canadian.’

Anyways. People are pissed about the cursory nature of both of these gestures. The classic, ‘we asked for defunding the police, reparations, land back,’ and got a national holiday. I’ve heard some folks on Twitter remark that it doesn’t have to be an ‘either/or’ game since a lot of activists have asked for these days to be recognized (and not recognized) in new ways. I think symbolism is important to reshaping culture, but everything is confusing with late-stage capitalism (i.e. Pride month pinkwashing). Nevertheless, Malcolm X did leave us with these words of caution, ‘The white man will try to satisfy us with symbolic victories, rather than economic equity and real justice.’ Justice is a recognition, reckoning, and reorganization of material power; until then, these gestures are flicking pennies at best.

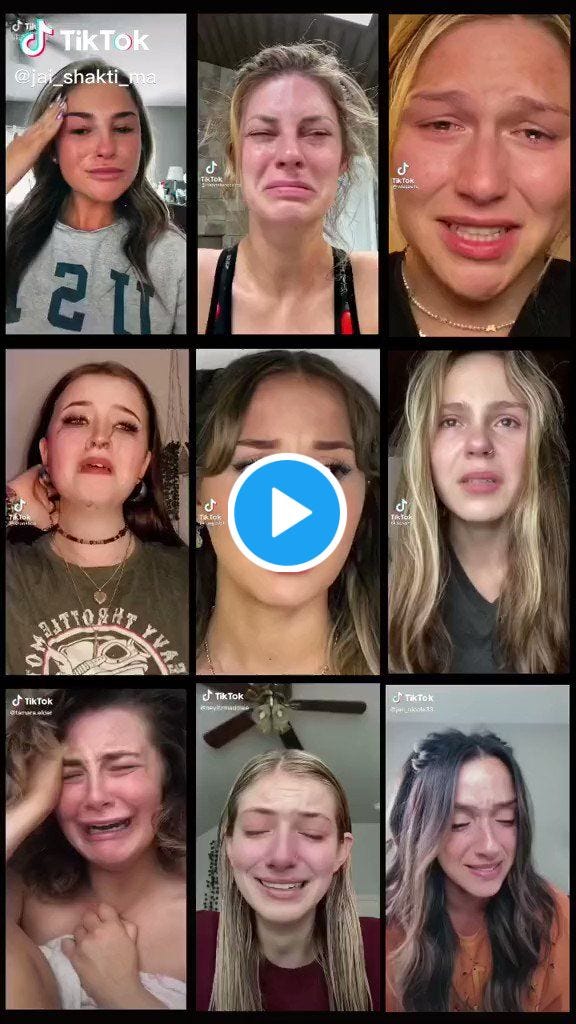

Speaking of performance there is a trend on TikTok right now where white girls are performing tears until the music drops and their face turns stone cold. As Twitter says, the weaponizing of white tears have officially been exposed and proven, by the ones who use the weapon against Black men, the most. Like everything, there is a shadow side to performance too.

Crisis capitalism: When the US catalyzed a global recession in 2008, hedgefund, BlackRock lobbied to shift policy in their favor to acquire distressed properties at knock-off prices (i.e. from all the people who were sold junk mortgages and eventually could no longer afford their hugely leveraged loan). They catalyzed a global housing crisis as depicted in the 2019 documentary Push (great watch!) and guess what, they are at it again, basically catalyzing a situation where houses have become unaffordable to buy as a family, but perfectly suited for a corporation. Crisis capitalism at its disgusting finest.

And lastly, don’t forget: