At some point in the deluge of the first week of the lockdown last year in March, there was a letter being circulated that had been written by an infectious disease specialist. It was typed up on an old-school blog and read like something that a parent might handwrite; gently forewarning our vulnerable and frightened inner child of what may lie ahead.

I have looked everywhere for the letter: on google, on slack, in my Whatsapp history, but I can’t seem to locate it. In the letter, there was a line that stuck to the part of my brain that is both vigilant and dissociative: ‘you will know someone who dies.’ There wasn’t much of a qualifier with the definitive statement, and there was no guidance about who the someone might be and how the impending and unexpected death might hollow you. At that point, everyone you loved was a target of the coronavirus’s wrath. It was an unnerving time.

As the weeks and months passed, a few people I knew caught the coronavirus, but managed to pull through the weary symptoms. A friend’s uncle tragically passed away in Bangladesh, and my Twitter feed was congested with old connections in India sharing the news of friends, colleagues and family members that succumbed to the virus in the hysteria of the dire shortage of oxygen that plagued the country. Anyone I knew in New York suffered the fate of knowing someone who died.

In Canada, our culture of relative compliance, the benefit of lower density cities, and lockdown measures that stretched out much longer than other places in North America kept the death rate nearly half of that in the US, though the number of total cases remained proportionally similar. To date, nearly 30,000 people have died from the coronavirus in Canada.

These statistics meant that depending on your privileges, the someone you knew who died from coronavirus was at least 1-2 degrees of separation, creating a distance from the suffering that was happening within the corners of isolated homes, families and communities. It became easier for folks to argue that the virus ‘wasn’t that bad,’ that people were ‘overreacting,’ that the government was trying to control us, that it was only impacting the elderly, and that the death rate was the same as the annual flu (false) - without fully considering the behind the scenes measures and choreography that might have contributed to containing the outbreak.

Perspectives on the nature and ‘science’ of the virus and the series of public health measures that transpired after the outbreak have become so charged with personal narrative, I can already anticipate the eye rolls happening right now. Ultimately, I trust the doctors and nurses on the frontlines. The ones in the arena that treated patients in hallways and closets, who held up iPads for families separated to say final goodbyes to lives cut short, who pleaded for citizen cooperation on any social media platform that would listen, and who are still living with the PTSD of seeing a virus ravage the respiratory systems of healthy individuals within hours. I honour their expertise, sacrifice and perspective.

And still, as we begin to transition from a pandemic into endemic, it is clear that the global health crisis is a memoir of systems failure and community ingenuity. For years, we will see the residual impact of people-powered movements that led to mutual aid infrastructure, workers rights, mental health destigmatization, online support circles, and the divinity within protests of every shape. We will draw on the actions that felt closer to the spirit and truth of what it means to be human, to be connected and held, even if they never make their way to policy.

-

On some mystical level, the pandemic felt like a warm-up to the other ‘crisis’ we are living in, but depending on where we live, have the privilege of distance from the intimate suffering. We’ve sort of collectively agreed to call the crisis, climate change, but I am reticent to use the term, since it relegates a major transformation of the living world as ‘weather threatening humanity.’ Sure, we might offhandedly comply that ‘we’ve f**ked up the planet,’ but we’re less willing to accept that when an organism, like a human, like a planet, has been violated, abused, exploited, sucked dry of its energetic resources, disrespected and made to feel unbearably unsafe, until all of its resilience has been burnt to the ground, its natural instincts will be to die and transform.

The earth is transforming. It always is, but there is a nature to the current pace of change that has become alarming because of its threat to the ‘longevity’ of humanity. We can’t know what is on the other side of its transformation, but like any living organism, it has a right to change and evolve into a state it considers necessary, maybe even more honest.

Right now, Glasgow, Scotland is the gathering site for what Prince Charles, the heir of colonialism called, ‘the last chance saloon’ to save the planet, otherwise known at the 26th edition of the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties. This event is taking place just a few weeks after TED’s ‘The Countdown Summit,’ where Lauren MacDonald, a Scottish activist, walked off a stage shared with Ben van Beurden, the CEO of Shell, in tears after expressing she did not agree with giving this man a platform to ‘greenwash’ climate change, and that her soul could not bare to share space with him.

Usually, I would call this event a gathering of ‘world leaders,’ but I am feeling especially defiant today, and am unwilling to see these folks occupying the table and headlines as anything more than the weakest and most spiritually depraved. Folks so disconnected from their humanity, and the innate power of existence, they have manufactured it at a scale that is squeezing the earth of its will to live, to serve, and be in relationship with one of its dominating species.

Watching COP26 feels like watching Real World Glasgow, except there are consequences. You endure the banal conversations for the entertainment of the occasional train wreck. At the forefront of the show was Jeff Bezos, the ambassador of labour exploitation and overconsumption, being congratulated for announcing a $10 Billion self-named fund (The Bezos Earth Fund) to ‘fight climate change and protect nature.’ The way I sinisterly laughed when I watched this…

The big news has been nation commitments around divesting from coal, the largest contributor of fossil fuel emissions, and international oil and gas projects (though China, Japan, India and Australia opted out), investing $19B in reforestation, keeping global warming under 1.5ºC, slashing greenhouse gas emissions and supporting Indigenous leaders protect biodiversity and defend land. Largely absent from he conversation was divesting from animal agriculture and the impact of individuated transportation.

‘Indigenous communities make up 5% of the global population, and 80% of the planets protectors of biodiversity’ - this is a statistic that has been floating around the Internet. In 2015, the Paris accords ‘legally’ recognized the crucial role of traditional knowledge and innovations by Indigenous peoples in tackling the climate crisis so that they could participate and influence international policy in a more meaningful way. But according to Indigenous activists at COP26, many of whom protested the over 1,000 deaths of Indigenous land defenders over the last six years, the gesture is vacant and token at best.

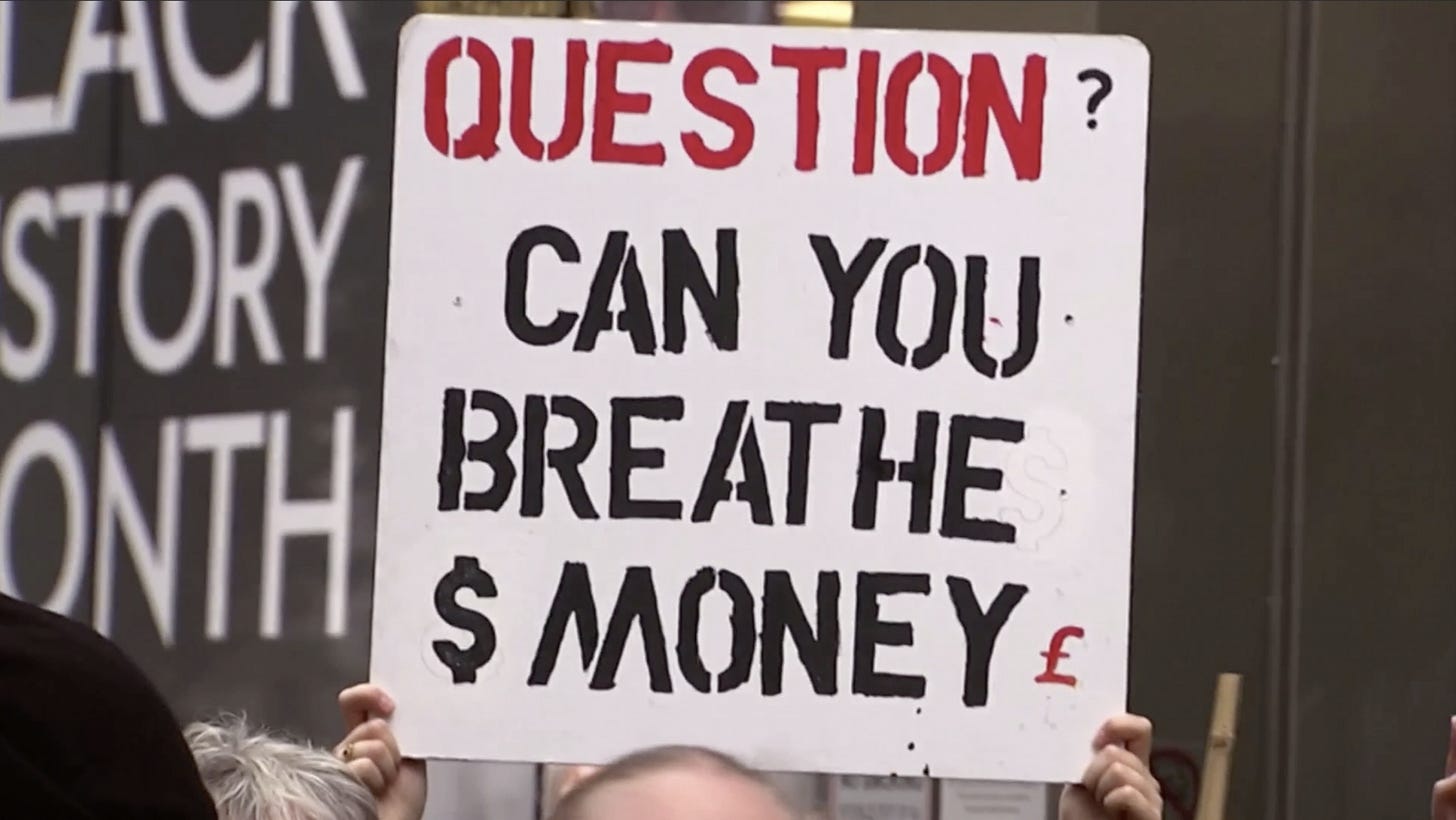

At the heart of COP26, like most international gatherings, is business and economics. Even at the proverbial ‘end of the world,’ managing carbon emissions have been turned into a market, the New York Stock Exchange launched a new asset called ‘Nature-Asset Class’ to offer profit from maximizing the ‘ecosystem services that a land provides,’ and many countries commitment to ‘protecting 30% of the land’ has often looked like further dispossession for poor and Indigenous communities.

I am not surprised by these antics. Can mostly white leaders, meeting in board rooms, negotiating deals on behalf of the land, using colonial and rational tools of planning, with a complete absence of the sacred, who have taken no personal accountability or remorse and perpetuate a paternalistic notion of saving, produce any other result? Can a rotting table ever produce the miracle of fruit?

This circus brings me to a question that Dr. Bayo Akomolafe, a philosopher, poet and public intellectual asks, ‘is the crisis the climate or how we approach the crisis? and the Lordeism, ‘the masters tools will never dismantle the masters house.’ In Dr. Akomolafe’s commencement speech to the 2021 graduating class at Pacifica - a profound work that I have read half a dozen times - he invites us to consider that the world must end - not necessarily in the apocalyptic way we have been programmed to imagine, but in the way that the world has ended many times, and for many people, ‘to make room for whiteness.’ He reasons that these climate commitments must fail, because we need the cracks in the fabric to find a new way, to meet each other and the earth again. ‘When things are urgent, we must slow down,’ he guides.

Txai Surui, a 24-year old, Indigenous activist from the Brazilian Amazon took the podium at COP26 and shared that her father told her to listen to the stars, moon, animals and trees. "The Earth is speaking: she tells us we have no more time," she says. If the earth is transforming, how might we transform with it? How might we follow its lead, its rhythm, its pace, and texture into an evolution? How might we flow with the ecstatic, improbable and imperceptible change within fractals of organisms? Have our ‘leaders’ repent to the Banyan tree, listened to the messages in a 24-hour wave cycle, witnessed a fire thirsty for clearing, stood at the centre of the monsoon to feel a planets reprieve and might we expect this from them, from ourselves? How might we declare Indigenous communities our ‘chosen leaders’, without permission, without election? If our bodies perish into ash, expand the mycelium, restore the roots of plants that become trees, that serve another version of humanity - is this still death? Can we ever truly die and how would we live and ‘crisis’ if we allowed this to be true?

We are living in rich, strange, and prophetic times. Self-preservation, scaled to ‘corporate interests’ will kill us, and though we may ‘die’ anyways, it won’t be with dignity. Our long-time denial of the earth’s transformation, of climate change - whether it was catalyzed, caused, inspired or sped up by humans, we will never know - is no different than our denial of a deadly virus, of nature’s power, of the ways in which we use control to deny how scared we are that we are powerful and powerless, that we are connected, disconnected and alone, that this world may never fully satisfy us, and that all these states, in their comfort and discomfort are equally vital.

As the earth continues to evolve and transform its operating system, someone you know will die. Maybe it will be me, maybe it will be you. Most likely it will be those we continue to keep vulnerable and precarious to maintain our comforts. But hopefully, it will be our psyches, our false selves, and the systems that hold the inner illusion together, so that the brilliance at the margins, humans and more-than-human species, can glow in ways that tables at Glasgow simply can not handle.

Much love,

Hima

This week in tweets

If you value what you read and would like to support my work, consider Buying Me A Coffee, leaving a heart/comment on this post below, or sharing this journal with another human. THANK YOU, LOVE YOU.