If you value what you read and would like to support my work, consider Buying Me A Coffee, leaving a heart/comment on this post below, or sharing this journal with another human. If you’re not a subscriber yet, join us!

THANK YOU, LOVE YOU

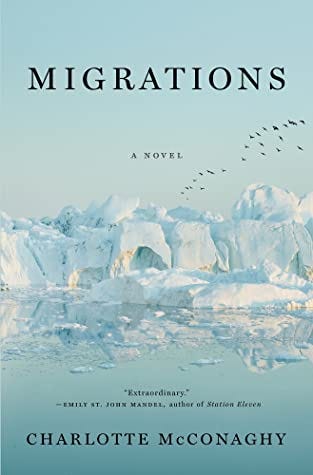

#HimaReads

This month, we will be reading Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy - a speculative fiction story about Franny Stone, who seeks out the last flock in the Artic terns in what might be their last migration. DM me if you are going to join <3. We will discuss at the end of the month.

We have been subletting a friends place in the city who has turned their backyard garage into a cabin. In the centre of the converted car park, a futon dressed with a colourfully woven blanket faces a wood-burning fire wrapped with enough supply for a month. Beside the fire sits a vintage record player loaded with Run DMC’s cover of Mary, Mary from 1988 and a chalk board, presumably filled in by friends over the years, with the words ‘The Great Escape’ circled. A disco ball churns on top and occasionally the wind crashes into the metal exterior like a bird flummoxed by a sprawling city.

The cabin has become our little urban sanctuary during these cold months, made colder with this latest phase of the pandemic. While watching Station Eleven this past week, the post-apocalyptic mini-series based on the book by award-winning Canadian novelist, Emily St. John Mandel, it has at times also felt like a bunker. On several occasions after an episode, each one like a short-film, we held each other across the futon with a tender silence cut by the song of a cackling fire. This kind of existential angst would be expected after watching a show about 99% of humanity dying from a flu, but the difference in this moment is how close it feels to the skin.

Emily wrote Station Eleven in 2014, and won the Arthur C. Clarke Award for best science fiction novel. I haven’t read the book, but unlike the television series, the story is set in Toronto where a mixed race couple has gone to see King Lear being performed at the Elgin Theatre; a scene that is literally and figuratively close to home. In the fourth act, the main actor, Arthur Leander, who is playing Lear, drops dead on stage, tying together the beginning of mass death, his enduring web of social connections and the Shakespearian theme that cleverly runs through the novel and show.

Show-runner, Patrick Somerville, began to adapt the novel into a film in 2018 but failed, eventually revising it into an anthology series and filming the first two episodes in January and February 2020, just as the COVID pandemic began creeping across the world. The timing of the series is both brilliant and eerie, and it settles as either a prophecy for what might be to come or as a reminder of just how close we were to an inevitable end. Unsettlingly, it is not as difficult to imagine the end of this chapter of humanity as depicted in Station Eleven then it might have been two years ago, which is perhaps what makes the show so poignant and unshakeable.

Though Station Eleven was pitched as a post-apocalyptic show about joy, the question it really explores is how do we go on? Before Arthur dies while playing Lear, his ex-wife Miranda pays him a visit to drop off a finished copy of her graphic novel, Station Eleven, which the show is named after. The graphic novel was a project that Miranda worked on while her and Arthur were together, but set on fire the day they unceremoniously broke up. ‘I started over’, she tells him about the story that she wrote slowly, privately and meticulously as a life-long meditation on the grief she became when her entire family died in a hurricane before her eyes as a child.

She gives Arthur two copies; the only ones that make it out into the world before she also succumbs to the flu days later. He gives one to Kirsten, his precocious 8-year-old co-star in Lear who he cares for on set like his own child in the absence of a relationship with his son, Tyler, to who he manages to send the second copy. When the electricity eventually lapses after the outbreak and the lights and Internet cut, the graphic novel becomes Kirsten and Tyler’s remaining artifact of life before the ‘end’, and Miranda’s transmutation of loss becomes the guide in making sense of their own as two of the few to survive. Over time and in a sluggish in-between, the story of Station Eleven becomes almost necessarily religious on their individual paths. Tyler is taken as a prophet by orphaned children who find family and community in living out the story and characters of the graphic novel. The children are willing to follow his orders, even if destructive, to uphold the sense of safety and meaning they find within the story and with each other.

'I remember damage, then escape, then adrift in a stranger’s galaxy for a long time'

‘There is no before,’ is a line from Station Eleven repeated by Kirsten and Tyler, almost dogmatically as an attempt to erase their unimaginable grief as they cope with trying to survive as young people on an open and hostile road to nowhere. The story of Station Eleven is a torch and a blanket, putting language to the unfathomable in the daily process of rebuilding. Yet, as they mature, and twenty years after the end, the story begins to unravel as they are thrusted and brave more deeply into ‘the before.’ The people they love and their moments of shared bliss and acidic rupture live on in their bodies through time, no matter how much they try to chant it away. It turns out, there is a before, but only when it is ready to exist in the present.

Kirsten joins the travelling symphony, a theatre group she finds shortly after suddenly separating from Jeevan and losing Frank - the two Indian brothers who unexpectedly become her caregivers during the short chaos of the outbreak that kills her parents. Together, in old army jeeps and with camping gear, the symphony tours a path around Lake Michigan that they call ‘the wheel,’ performing Shakespeare plays with the devotion to story, art and craft as necessary oxygen. They bring music and community to the places they visit, which otherwise are starved for such delights, and live out their motto that ‘survival is insufficient.’ In these dark times, they have tasked themselves to turn the lights back on, almost always performing at nightfall. Shakespeare survives the end, becoming shared language and purpose, and the performance of tragedy with humour becomes the place to hold and express their own.

The symphony is Kirsten’s family, her home. She is quick to shoot a dagger at anyone who threatens them; a skill she learns after the ‘first 100 days’ when the world is dangerously primal. She protects them with the ferocity of her fear of ever experiencing loss again. This makes her as fiercely loyal as she is indignant when anyone expresses their desire to take a break from the wheel, to leave, to try something new. Her story of coming into grace with the inevitability of change, despite so much change, parallels her capacity to revisit and relive moments of great loss and close the wounds with the words that were left unspoken in the disarray of a species dissolving. Through the show, Kirsten returns to the softness visible when you first meet her backstage at King Lear, an essence snatched from her in a world that turned as cruel to ‘outsiders’ as it was caring to ‘insiders’, in its will to survive.

'To the monsters, we are the monsters.'

Between the graphic novel, Station Eleven, and Shakespeare plays like Lear and Hamlet, the show dances between the need for new stories to make sense of an ever-changing present, old stories to bear our connective tissue across time, and the discernment to know when each are helpful or harmful to our survival, our joy, our healing. In this way, there is no end, because the stories live on across and through all material destruction - as books, as memory, as scripture, as living memorial and as embodied recognition of all that stirred the heart.

Every evening after watching an episode, the anticipatory loss hit me. The ache of not saying goodbye or seeing my people one last time in a pandemic that could have moved through us at a completely different rate felt entirely palpable, swelling my senses. C and I looked at each with glazed eyes that understood we very well could be each other’s companion and crutch in whatever end times we find ourselves in. Pandemics have wiped out entire populations tracing back to the Roman Empire, in a way that feels like we could look back on this time and consider ourselves lucky.

I will probably watch Station Eleven again and again - if anything to get closer to the condition that makes us delicate and entirely destructible in a matter of hours as it does infinitely resourceful in the pursuit of connection and aliveness, and how the intimacy of this knowledge is the only place where compassion can grow and serve from. The more we are unwilling to contend with our frailty, the more stories we will write, and enemies we will characterize, to protect us from the truth of our physical impermanence. Maybe we need these stories right now to survive, as Kirsten and Tyler needed Station Eleven, but eventually, the cracks in them will appear. For some, the pandemic was that crack.

Much love,

Hima

#ThisWeekinTweets