If you value what you read and would like to support my work, consider Buying Me A Coffee, leaving a heart/comment on this post below, or sharing this journal with another human. If you’re not a subscriber yet, join us!

THANK YOU, LOVE YOU

My friend A says it is good for his mental health. S says it is less physical labour, but more emotional labour and K says everything is figure-outable. These are some of the conversations we have in the lead up to deciding to move into a co-living house with 6 other people in the west of Toronto.

In December, we go through an application process, detailing everything from how we tend to make decisions, how we intend to spend our time inside and outside of the house, and what skills we can bring to the community. I share that I am introverted and can be moody, but down to throw all the themed parties; a contradiction that satisfies my astrology. While in Helsinki, we jump on Zoom with the house for two hours, trying to get a sense of whether we could live together; whether we want to live together.

Food is at the top of C’s mind - a topic that has sometimes meant weekend-long retreats for the house to figure out how to mindfully and sustainably buy and dispose of the shared food model, while meeting everyone’s needs for comfort, pleasure and dietary preferences. S tells me a gardener will be coming to the house over the summer to teach everyone how to grow their own food. This is collaborative work that seems daunting, but also crucial if we want to put a tiny foot forward towards re-wilding and healing the land from decades of extraction. My spirit lights up.

I share all of my fears, and there is a laundry list. Will I be able to sleep? How will I have friends over? Will there ever be silence? Is there a cue for the shower? At the top of my list is an existential question about what it means to be an adult, and how to find the confidence to live your own script. Making smart speculative investment decisions and getting into the housing market before it’s too late are two sentences that play in my mind like a form of torture. Are we making a mistake by not doing so, and will I regret this?

At the same time that the conversation around co-living has grown, Toronto has become the priciest and most fiercely competitive real estate market in Canada, with the average home selling for $1.260M. In two decades, prices have increased by 490%, and are expected to go up by another 12% this year alone. Some are calling it a crisis housing bubble, that will cause misery and ruin if it crashes, but the Bank of Canada contends that it is not so. The FOMO of entering the market has led to a rise of what economist, Benjamin Tal, calls using the bank of mom and dad to firepower offers and competing bids. My dad tells me he wants to help. He is nervous we won’t be settled or have a place to live before he passes. Every week I get emails and Whatsapp messages of listings.

Many have accepted that the housing market has become out of reach or they simply refuse to carry a hefty mortgage for a 1-bedroom condo, instead choosing to focus on alternative investment opportunities. We rarely refer to community and care as investment opportunities, even though we hope for an ROI from the risk of love and the cost of time that we pour into them. Commercial developers are becoming increasingly interested in meeting the ‘millennial demand’ for co-living, who are simultaneously questioning everything from relationships to work to housing to money; writing new narratives of meaning.

Everyone I tell that we are moving into a co-house is equally shocked and intrigued. Why would you do this? What is the purpose? I could never. The common assumption is that we have made this decision to save money, which also suggests that our shared definition of being wealthy is to have the right to private space and property. I take this personally, and an ancestral shame around wealth and worthiness wells in me so deeply, there are simply not enough tears to carry it. There are of course cost-savings to co-living given the economics of sharing, but it is not as much as one would perceive.

Would I buy a big old fancy house if I could afford it? Probably. I’m not judgemental of this decision, because we are living in bardo times, the place in-between stories and scripts. The middle class especially can post about anti-capitalism in one breath, support an affordable housing strategy in another, read a book about genocide and stolen land, and hope their stock investments triple at the same time. This confusing existence, of figuring out how to live and embody the radical dreams we speak of, like housing justice, will be a defining marker of this era. It means that some will have to model a different way; an additional way. Because an actual transformation of housing in urban cities would mean building a market outside of speculation and expropriating private land for public use and Indigenous stewardship, which is equally impossible to imagine in the current state, and also entirely possible considering the levels of instability we are playing with.

When I tell my parents about our decision, they don’t say much. My mom grew up in a ‘joint family’ with her father’s sibling and their family - a common living arrangement amongst Indian families. Even after my parents were married, they lived with my paternal grandparents for many years. When they left the UK for Toronto and bought their own single-family home, it was an act of subverting the extended family structure to pursue their own ambitions and care for their mental health even though the trade-off meant cutting off support and intergenerational exchange.

David Brooks chronicles the history of the decentralization of the family in his piece, The nuclear family was a mistake. He shares how as the pace of life sped up, family loyalty was exchanged for privacy, convenience and mobility, ushering in the single dwelling nuclear family structure, which is typically two parents with two children constantly living on the edge of balancing full lives. The fragility of the nuclear family, Brooks argues, then led to further fragmentation, into ‘single-parent families, single-parent families into chaotic families or no families.’ He summarizes the change in family structure as this:

We’ve made life freer for individuals and more unstable for families. We’ve made life better for adults but worse for children. We’ve moved from big, interconnected, and extended families, which helped protect the most vulnerable people in society from the shocks of life, to smaller, detached nuclear families (a married couple and their children), which give the most privileged people in society room to maximize their talents and expand their options. The shift from bigger and interconnected extended families to smaller and detached nuclear families ultimately led to a familial system that liberates the rich and ravages the working-class and the poor.

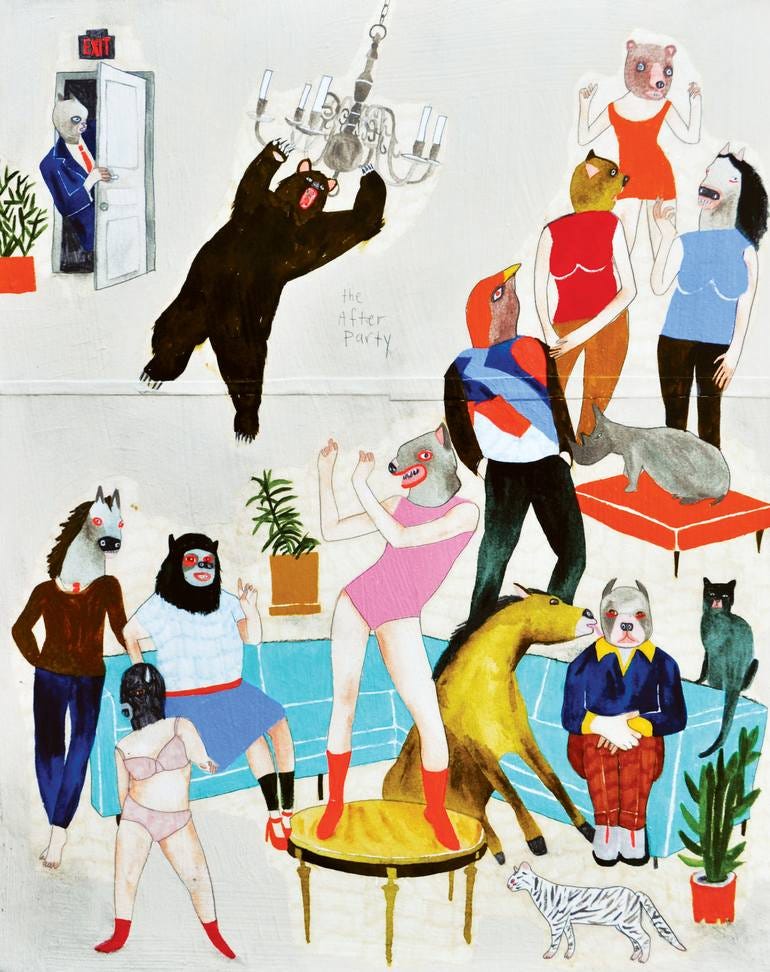

Co-living in contemporary times is a return to the ‘extended family’ but the difference is captured within the choice and intention to pursue it, versus having to endure it within the confines of cultural obligation. Within the choice is ideally the opportunity for relational growth from addressing conflict in healthy ways, setting boundaries and communicating needs, instead of simply biting one’s tongue until it severs whole. In some ways, this decision feels calculated within the DNA of my lineage as an enduring value for community, closeness and intimacy. I am fascinated by the ways the pendulum swings across generations. Perhaps, we stay the same as we evolve.

Despite this extensive period of processing and deciding, I am freaking out. This past weekend I call an emergency meeting with some of my new roommates. I have stayed up late reading Jennifer Seniors piece, Why your friends will break your heart, where she reflects on the brutal pain of friendships dissolving, and the ways in which this relationship that is often referred to ‘as beneficial to your health as giving up cigarettes,’ is increasingly fragile in a world where everyone is running in different directions. ‘One could argue that modern life conspires against friendship,’ Seniors shares.

I have written about the friendship renaissance, and even was on the Life Without Us podcast (who not coincidentally is led by one of the founders of this co-house!) to dig deeper, and still, I wonder, how close is too close? The language of ‘chosen family’ has become popular, especially amongst queer communities, but my therapist reminds me of the dangers of projecting family roles on friendships. ‘If our friends become our substitute families, they pay for the failures of our families of origin,’ Seniors writes. It’s not surprising that we seek friendships that emulate our early imprinting, as we do in marriages according to Freud, but if not acknowledged, it can go horribly awry.

I know there will be conflict while co-living. I am scared about my capacity to face it, to transform it, to not let the weight of it destroy me or my friendships. Will my conflict skills improve or fail me? I fear my hypersensitivity and how I assume anyone who is mad at me will leave me. The risk-reward ratio is high and I am not aloof about this. Yet, in the midst of my meltdown, I am reminded of what could await me on the other side: new rituals, more intimacy, shared labour, and the love generated from co-creating. I remember that relationships are not ensured - they never can be, and if something is to break, it will. Co-living or not.

We have committed to trying it for a year. ‘I can do anything for a year,’ I boast. ‘It will make for some good writing,’ I joke-ish. Stepping into the unknown is always terrifying, but we do it because we know there is something there for us, even if we don’t know exactly what it is. I am excited to find out, even though it scares me to death.

Much love,

Hima

#ThisWeekinTweets