If you value what you read and would like to support my work, consider Buying Me A Coffee, leaving a heart/comment on this post below, or sharing this journal with another human. If you’re not a subscriber yet, join us!

THANK YOU, LOVE YOU.

#HimaReads

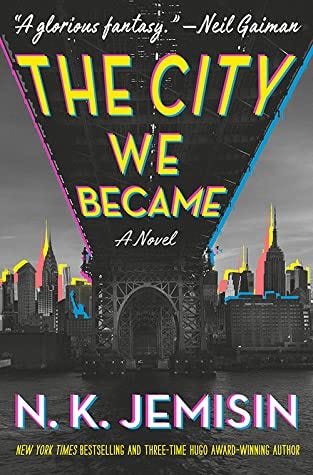

This month, we will be reading The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin, which is an urban fantasy novel about the great city, New York, becoming sentient and five locals coming together to defend it.

‘They’ve declared the crow extinct,’ Niall Lynch, the Irish professor and researcher working fervently on trying to prevent the mass extinction of animals and birds, solemnly tells his beloved, Franny Stone, in Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy, the first book in my monthly science fiction reading series.

The story is a haunting portrait of a wandering Australian-Irish woman desperately trying to save the few remaining Arctic terns by following them on their final migration across the world. Arctic terns make the longest migration of any animal - flying from the Arctic, all the way to the Antarctic, and then back again, within a year. Over an approximate thirty-year lifetime, they will travel the equivalent of flying to the moon and back three times. Their courage and sheer fortitude enamour Franny; a love she inherited from Niall, though her devotion to birds began much earlier in life when she defiantly fed the crows in her backyard as a child. Soon, the crows began to follow her, to and from school, bringing her gifts in exchange for food for four years. ‘Even when I forgot to feed the birds they brought the gifts. They were mine, and I theirs, and we loved each other.’

The gruelling expedition begins in Tasiilaq, Greenland, after Franny shrewdly convinces a crew of fishermen, and captain Ennis to take the journey along the migration path. The plan is to intercept the Arctic terns along the way and gather any data that might be useful in protecting their survival. By now, in the world at the time, most of the creatures across the land, sky and sea have been killed or fished almost to extinction largely due to burning fossil fuels. ‘A nameless sadness, the fading away of the birds. The fading away of the animals. How lonely it will be here when it’s just us.’ In the story, there is no indication of ‘when’ this future time is, and could easily be as close as today. The scientific community, including Niall, self-loathes about the current state often failing at trying to balance despair and guilt with optimism. ‘The world would be a better place if it was humans we could stuff and pin-up and study',’ he says with angered pain about the indifference to prioritize economic growth and greed over extinction.

The loss of life that surrounds and churns Franny, mirrors her own history of unimaginable loss. After boarding the Saghani (meaning Raven in Inuit), she must summon the fortitude to live through the physical beatings of being a sailor. Bruised hands from tying knots, dangerous currents and freezing wind bites are just the beginning. For a long while, Franny resents the sailors for continuing to fish an emptied ocean, even though she needs them. ‘Why don’t any of you seem to care about what you’re doing?’ she darts at one of the crew members. When a big catch becomes imminent, she coils, ‘am I really going to stand here and watch as these creatures are slaughtered? How are they different from the birds, whose lives I might very well give my own to protect?’ But over time she relates to their almost obsession and learns that giving up an identity and vocation across family lines is not as simple as a moralized duty. ‘I don’t think they’re scum — against all my better judgement I’m actually starting to like these people - but there’ll always be a part of me that’s disgusted by what they do. Maybe once upon a time, the world could tolerate the way we hunted, the way we devoured, but not anymore.’

The sailors know they must stop fishing, but they also don’t know who they are without the thrill and salt of the sea. ‘They are migrants of land and they love it out here on an ocean that offered them a different way of life.’ It is also their income source and only skillset and indicative of the amount of effort that will be required to transition purpose and support workers as they are increasingly replaced by automation or decommissioned to reprioritize the land. In 2020, TIME magazine was already writing about how the pandemic had created a strong incentive to replace the work of human beings, estimating that 2 million manufacturing jobs will be performed by robots by 2025.

Despite many setbacks on the journey, including machinery breaking, running out of food and water, and sanctions being applied on boats to end fishing - Franny is undeterred. ‘It’s a relief to at last have a purpose,’ she shares as she recognizes herself as a migrating bird, but one without a destination. ‘I leave for no reason, just to be moving, and it breaks my heart a thousand times, a million.’ In the nights, inside the cabin under the boat the size of a closet, she writes to Niall, longing for his touch, his wisdom, to share in the holiness of sighting the birds, while slowly revealing their hypnotic love story. ‘We cling to each other, feverish. Perhaps, it’s the recognition of a second will, one to rival my own, but in his certainty, I find mine awakening, I find true adventure at long last, one that might just be enough to keep me.’ I assume he is unreachable while they are at sea, and she is left to paper and pen to connect with him.

Her mother’s abandonment by suicide when she is just 10, followed by living with her cold grandmother, the mother of her father who was in prison, leaves her equally with a disposition for risk as recklessness. She is almost always on the edge of drowning inside bottomless grief, which often surfaces as sleepwalking towards the death she dreams will relieve her, and relieve those who know and love her. ‘It’s not life that I am tired of, with its astonishing ocean currents and layers of ice and all the delicate feathers that make up the wing. It’s myself.’ But her proclivity for self-destruction is acquitted by her sincerity and devotion to protecting and knowing the living world. ‘And here is the undeniable truth: I have never feared the sea. I have loved it with every breath of me, every beat of me.’

The inclination to further protect nonhuman animals is currently being contested in the US by a case to grant Happy, an Asian elephant in the Bronx Zoo, habeas corpus, which is a petition used to report unlawful detention. As reported in the New Yorker by Lawerence Wright, if Happy was granted the habeas petition to move from the zoo to a sanctuary, she will be seen as a ‘person,’ versus a ‘thing',’ as the law currently states, and be given more rights. Wright calls the case an indication of ‘humanity edging towards a radical new accommodation for animals,’ pointing to examples all over the world of governments establishing specific rights for animals, especially those proven to be highly intelligent and sensitive, like elephants, apes and cetaceans.

The debate has surfaced questions about how animals might be accountable to the law, if self-awareness and capacity for friendship equate to personhood and if we should be equating rights on likeness to humans versus considering what animals uniquely need. Currently, animals are protected by welfare laws against abuse and as beneficiaries of trusts in death and divorce, but some, like philosopher and author, Peter Singer, who believes that the moral argument for animal equality rests on their capacity for suffering and happiness, feels ‘there has been relatively little progress in terms of real, on-the-ground change in the treatment of animals.’

There is a scene in the book where Franny has taken off to Yellowstone Park, leaving Niall behind, who compared to her finds his strength in work and responsibility, versus journeys or movement. The park is the last pine forest and is vacant of animal life. The deer have all died. The bears and wolves went long ago, already too few to survive the inevitable. It is a grim and unimaginable scene - and one that if factual might change the nature of our debates and the ways we consider how to be allies to the animal world. There is no birdsong as I walk among the trees and it is catastrophically wrong. I regret coming here, to where it should be more alive than anywhere. Instead, it is a graveyard.

In Candace Fujikane’s book, Mapping Abundance for a Planetary Future: Kanaka Maoli and Critical Settler Cartographies in Hawai’i, she carefully shares a Hawaiian ancestral methodology that maps the abundant relationships between humans and non-human beings that sustain life to counteract capitalist cartographies rooted in private property and borders of control. Foundational to these abundant maps is an art form called kilo, which records and forecasts the changes on earth, from rising heat to less rainfall and migration patterns, in stories and song, to ‘defend, nurture and preserve’ abundance. She suggests that an orientation towards kilo, abundance and wonder, and the care within Kanaka Maoli cartographies, is one way to establish more decolonial relationships with the land and respond to the climate struggles and ecological violence facing the world today.

As Migrations nears the final chapters, I find myself heaving as it is revealed that Niall had died in a car accident years prior. His final wish was to have his ashes spread somewhere along with the Arctic terns migration, lighting a fire in Franny after she had been released from prison for pleading guilty as the driver of the car, as a form of self-punishment. The trackers that Franny had put on the Arctic terns in Greenland to guide the journey are no longer working, and as she comes to terms with Niall’s death alongside an uneasy ocean, she also releases her attachment from finding the Arctic terns and for them having to survive such dire conditions. ‘So—for my own sanity—I release the Arctic terns from the burden of surviving what they shouldn’t have to, and I bid them goodbye.’ In their sweet and torrent love, the recognition for the other’s inner wilderness and wildness is ultimately what binds them.

Eventually, the Arctic terns are found. Ennis and Franny have survived the final leg of the journey, barely and against all odds, after they separated from the rest of the sailors. ‘Because it seems to me, suddenly, that if it’s the end, really and truly, if you’re making the last migration not just of your life but of your entire species, you don’t stop sooner. Even when you’re tired and starved and hopeless. You go farther.’ There are hundreds of Arctic terns feasting in the untouched waters along the coast of the Antarctic. She weeps, for the journey that has been made and all that was formed and left behind in its intoxicating wake and call.

Niall always felt that the less humans touch or interfere with animals, the better. ‘All our touching does is destroy,’ but Franny showed him and herself, that perhaps humans did not always have to be a ‘poison, a plague on the world,’ but that somehow we could nurture it too. Charlotte gave us a story that showed us the ways that devotion and destruction are two sides of the same coin and that often the fight to repairing the world is the way we repair ourselves.

Much love,

Hima

Did you read the book? I would love to hear your reflections. Send me a DM or leave a comment below.

#ThisWeekinTweets

Es una delicia leerte Hima, muchas gracias!